Our perception of Sufism is still shrouded with ambiguity and confusion. As it is still reduced anthropologically and ethnologically to esoteric methods, which has a system in mysteria and a way of entering the methodology. Also, its mechanism relies on a lexicon and a behavior, and its perceptual system stands on a narrative that is mostly religious or mythical, in the positive meaning of a myth as being a system of imagination, suggestion, and construction of spiritual images. It is also reduced to terms that were not invented by Sufis but by their critics and defamers such as “Incarnation and Union” or “Pathesim (unity of existence)”, but could Sufism be reduced to this anthropological and caricature image? Wouldn’t such an image pose a barrier to understanding the metaphysical and ontological dimensions on which Sufism speech was built, and of such speech we can find interpretations in philosophy, architecture, and fine arts? The common perception of Sufism (Tariqa, tombs, Awliyaa (God’s protégés), saints, seeking blessing, pleading,… etc.) clouds our vision as to what Sufism is which is generating the spiritual image in arts, literature, philosophy, and architecture.

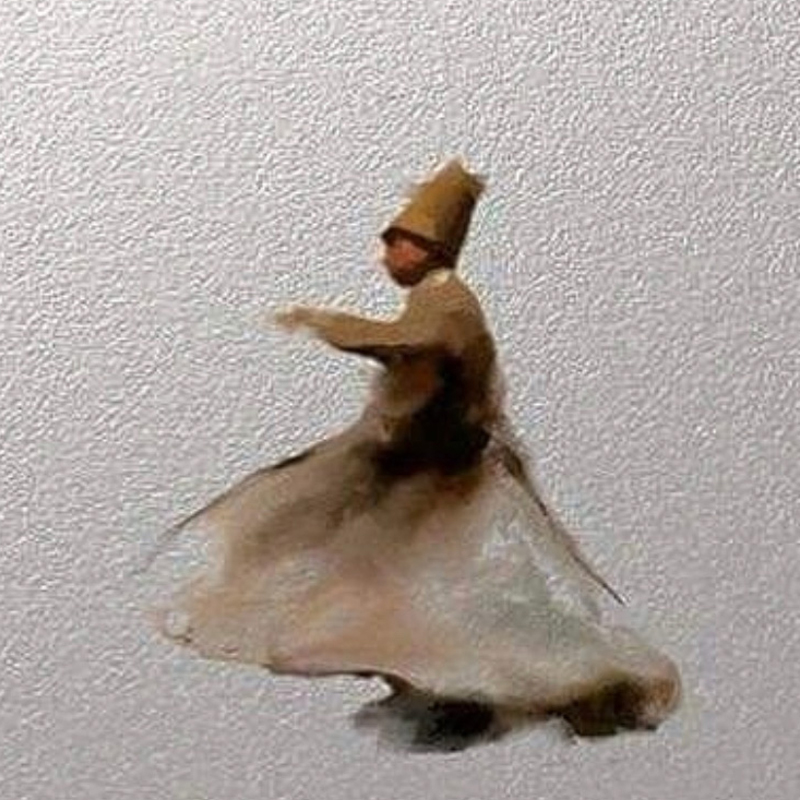

Sufism has indeed generated, during its long and troubled history, spiritual images depicted in construction (mosques, palaces, bathhouses “hammam”… etc.) in fine arts, especially Whirling Dervishes in Malwawiyya, according to Jalal Al Din Al Roumi (1207 – 1273), and in Bible Illustrations by Narc Shagal (1887 – 1985). If we ever got the chance to search for Sufism manifestations in architecture and fine arts, we have to resort to some of the principles of Christianity culture and Islamic Arab culture. Those principles could be summarized as follows: Similarity between Poetry and Painting Principle, Morphism of Human and Cosmology, and finally; Shapes and Circles Principle. In the end, we added an addendum containing highlights of the architecture and fine arts of Sufism impression, which is an interpretation of the world’s system in painting, and an interpretation of the image system in poetry.

The similarity between Poetry and Painting Principle

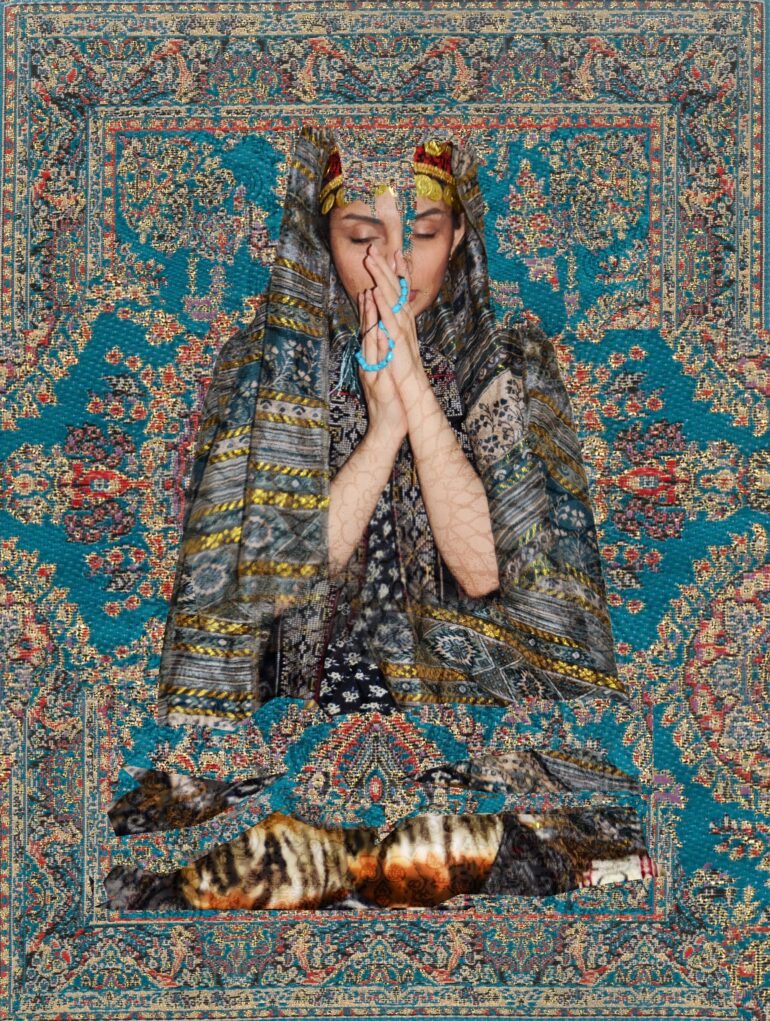

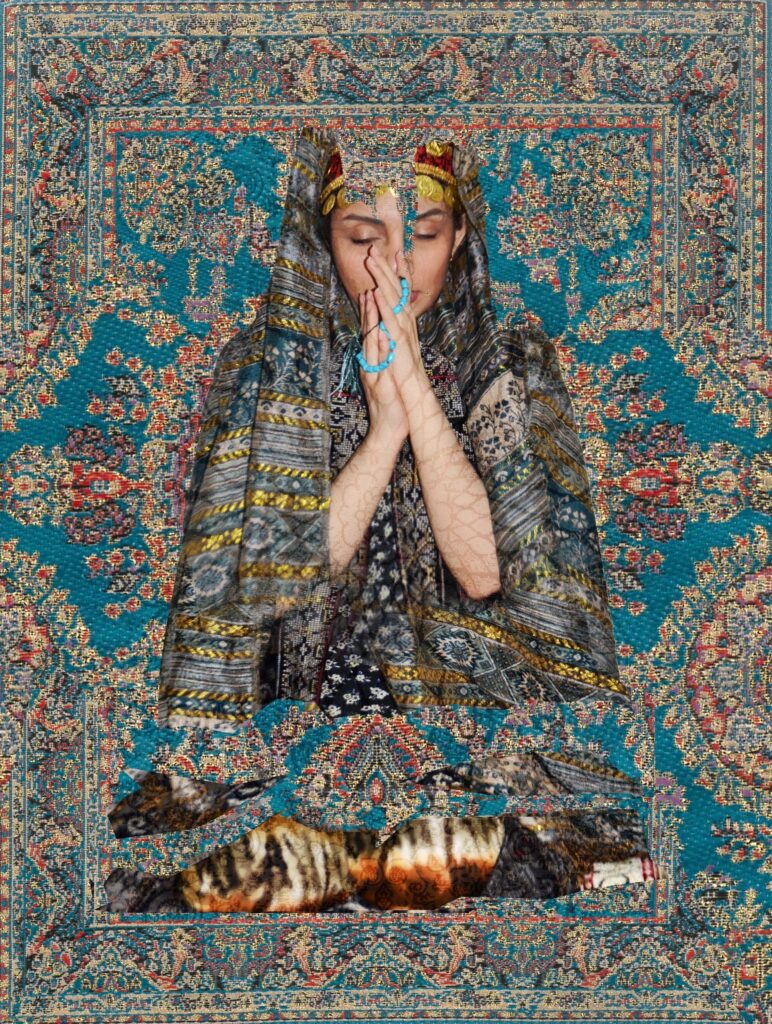

The word “Poetry is similar to poetry (ut pictura poesis)” is attributed to Horathius, the Romanist poet (65-08 BC), who inspired it from Semendious, who also said – but in some variation or chiasmus – “Poetry is a talking painting, and painting is a silent poetry”. Thus, the words of a poem are like colors in a painting. So, if this formula was known back in Latin poets’ times, and was established prominently by renaissance painters, what was it like in Arab Islamic culture? Did Sufism play a role in making visual images out of words, and in making readable phrases out of images? It is worth mentioning that Arab Islamic Culture had an “Iconoclastic” tendency, same as Judaism, meaning it was against image and figurations adhering to the Islamic narration that forbids image. Nevertheless, it was far from being aniconic, according to Christian Gruber (Ch. Gruber, 2010, p.5). On the contrary, Islamic history witnessed iconic attempts, manifested particularly in miniature art, and the art movements that Mahmoud Farghaly enlists (Islamic Figurations, 1991), which are proof of the growing interest in images and figurations, with variant levels of simplicity and complication. In addition to that, Mahmoud Farshchian, the contemporary artist, got the inspiration for some of his artwork from the ghazals of Sufi Shams-od-Dīn Ḥāfeẓ-e Shīrāzī (1325 – 1390 AD). In those paintings, the feminine theme and dark colors are overpowering and give the eye the impression that the world inside the art piece is in constant revolving and waving.

Still, the catholic Christians (and relatively orthodox) alone, in religious history, were expressly allowed to use imagery and sculpture after numerous and intense theological and religious discussions. Thus, the extensive presence of images in churches and cathedrals is strong and familiar as we see statues of Virgin Mary and Jesus, oil paintings of saints, and bible scenes creatively depicted by the brushes and colors of painters such as Raphael and Michelangelo during the Renaissance. Catholic indeed had a mystic vision of the world and society’s structure. The mystic perception is Iconophile at the core, a one that is fond of image and imagery whether in sculpture and painting or in finesse words and adorning poems. An example of sculpture and fine arts would be the Jesuits, led and founded by famous Sufi Ignatius of Loyola (1491 – 1556 AD) who were among the Sufis most fond of images and imagery, and the ones who utilized them the most in Counter-Reformation, and in their war against Protestantism. While in poems and rhetoric, it is clear in Nasrid dynasty era in Granada, especially artistic display of poetry in Alhambra Palace. Lisan Al-Din Ibn Al-Khatib and his student Ibn Zamrak of Andalusia were the ones who paved the way to adorning Alhambra Palace using, of no intention of their own, Horatius principle of the interconnectedness of painting and poetry, by allowing poetry to be “seen” and painting to be “read”. In Ibn Al-Khatib Book “Al Katiba Al Kamina Fi Man Laqinah Fi Al Andalus Min Sho’raa Al Ma’a Al Thamina”, Sufi poets occupy the forefront of the book as a considerably large number of them wrote poetry, such as Ibn Al Zayyat of Málaga who said:

Witnessing your inner self is a secret that is kept from you

If you were to unveil it, nothing else is needed

The upper, lower, and a little of both

A story at the highest point is unfolded

This is just the leading edge of the extensive presence of Sufi spirit and its poetic and architectural interpretations, or even the presence of the visual and architectural spirit in poetry itself. As we can see in this poem by Ibn al-Zayyat (upper, lower, story, point, Nasb “unfolding”) and also in “Construction of Circles” book by Ibn Arabi, which provides the finest example of the entanglement between the spiritual and geometrical. We could look at the inscription within The Mexuar at Alhambra Palace (Granada), and we would see “Only God is Victorious – Wa lā gāliba illā-llāh”, the motto of Nasrid dynasty, as well as Quranic verses that embellish the roofs and arches, or praises for Abu Abdullah Muhammad dynasty which ruled Granada. What drags attention there are Sufism-loaded phrases embellishing the walls of the halls, court, and arcade such as “Connected Blessing – al-ghubta al-muttasila”, “Ultimate Happiness – Al-Saada Al Tamma”, “Yumn, Baraka, Iqbal”, all written in Kufic script with inscriptions and Atairique (floral pattern). However, this was the extent to it in the Islamic West and Andalusia, and this was due to forbidding imagery and thus resulting in this scarcity of images and scarcity of the channels leading to them.

Entanglement between Human and Cosmology

This principle is most prevalent in palaces domes, as we can see in “Comrade Hall” in Alhambra Palace, Granada. The architectural dome is a replication of the sky with all its planets, stars, and celestial objects. In the hall, we can see a part of the 30th verse of Surat Al Mulk “And we embellished the lower world with lambs” embellishing the walls. Another line contains a poet by Ibn Al Khatib in which he says:

Day and night, on behalf of me, they greet

Mouths of wishes, fortune, happiness, and kindness

She is the supreme and dome and her daughters we are

Although I get favored and glorified in my class

I was undoubtedly the heart of those inner organs

And in the heart the power of spirit and soul is clear

And if my peers were the constellations of its sky

In me, not in them, lies the honor of the sun

This poem that embellishes the walls of Comrade Hall introduces the principles of entanglement between what’s human (the organs, the heart, the soul, and the spirit) and what’s cosmological (the higher dome, the constellations, the sub). This entanglement is as old as human knowledge, and it is fostered particularly by the Sufis who think that the human (the smaller world) and the universe (the greater world) are interchangeable and interconnected. This term was found in Nemesios, the Latin philosopher (420 – 350 AD), and was restored by Brethren of Purity in “Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity” and by Al-Jahiz, only to reach its peak expressions in Andalusia Sufism, especially with Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi when he said “Human is a small world, and the world is a great human” in “The Meccan Revelations”. Since fine art and architecture do not depict the world with all its celestial domes and objects, nor does it depict the human with his mental and psychological realms, due to their commitment to the prohibition of images throughout history and in fiqh, except for some Arabic miniature that distinguished the Islamic history, we might say that the human is hidden within the universe, rhetorically in what we call “enthymemes”. So human has enthymic presence within the universe phenomena as much as the universe is present within human’s features (how the skin and its wrinkles are similar to the earth with its steppes and terrains, also how the eye and its parts; pupil, retina, and iris are similar to the celestial sphere, etc.). Humans are only seen within the universe phenomena. Abu Zumruk was never afraid to speak in the singular 1st person pronoun in a culture that mostly uses the plural 1st person pronoun, and his poem blemishes the great dome in Alhambra Palace, in Kufi font, and in reverse so that it refers to the enthymic presence of the individual in the universe and how he is the mirrored image of the universe:

I’m a garden graced by every beauty

See my splendor, then you will know my true being

For Mohammad, my king, and in his name

The noblest of all, in the past or to come, I equal

Of me, a work sublime, Fortune desires

That I outshine all other monuments.

What pleasure I provide for eyes to see!

In me, any noble man will take fresh heart;

Like an amulet the Pleiades protect him

The magic of the breeze is his defender.

A shining dome, peerless, here displays

Evident splendors and more secret ones.

Gemini extends to it a touching hand.

Moon comes to parley

Stars clustering there

Turn no longer in the sky’s blue wheel;

In Abu Zumruk’s poem, the universe acts as if it is a human being, for universe is the greater human in Sufi expressions, as it borrows his states and imitates his actions: the Pleiades seeks refugee and protection from Allah, the Dome displays its splendor, the Gemini shakes hands, and the moon approaches to parley. The universe to Sufism is a living entity that’s in motion, the universe breathes God’s – most merciful – breath blown into creatures and matters. A Mawlawi portrays this life and motion in Whirling Dervishes, in a dynamic motion that creates concentric circles, and a static motion in fine arts. When Mawlawi whirls, he brings sky and earth together with his right hand pointing upwards and his left hand pointing downwards. His movement represents the linkage between man and the universe as he whirls and spins mimicking the orbits rotating around their axis, only to wander, and wandering is a most superior manifestation of wisdom. That is because he sees harmony in the depth of chaos and scatterings. Mawlawi combines spiritualism and aestheticism, as Shafique Farooqi provides artistically and poetically in his book (Farooqi, 2014, p.120). In the moment of Semah (listening), the universal love and self Wajd (affection) drive the movement of the body, whirling dervishes also combine opposites (mortality and eternity), and it highlights the circular nature of existence. Farooqi’s paintings reflect this aspect of Mawlawi’s ascendance and rising towards the universe by discarding his ego and embracing existence.

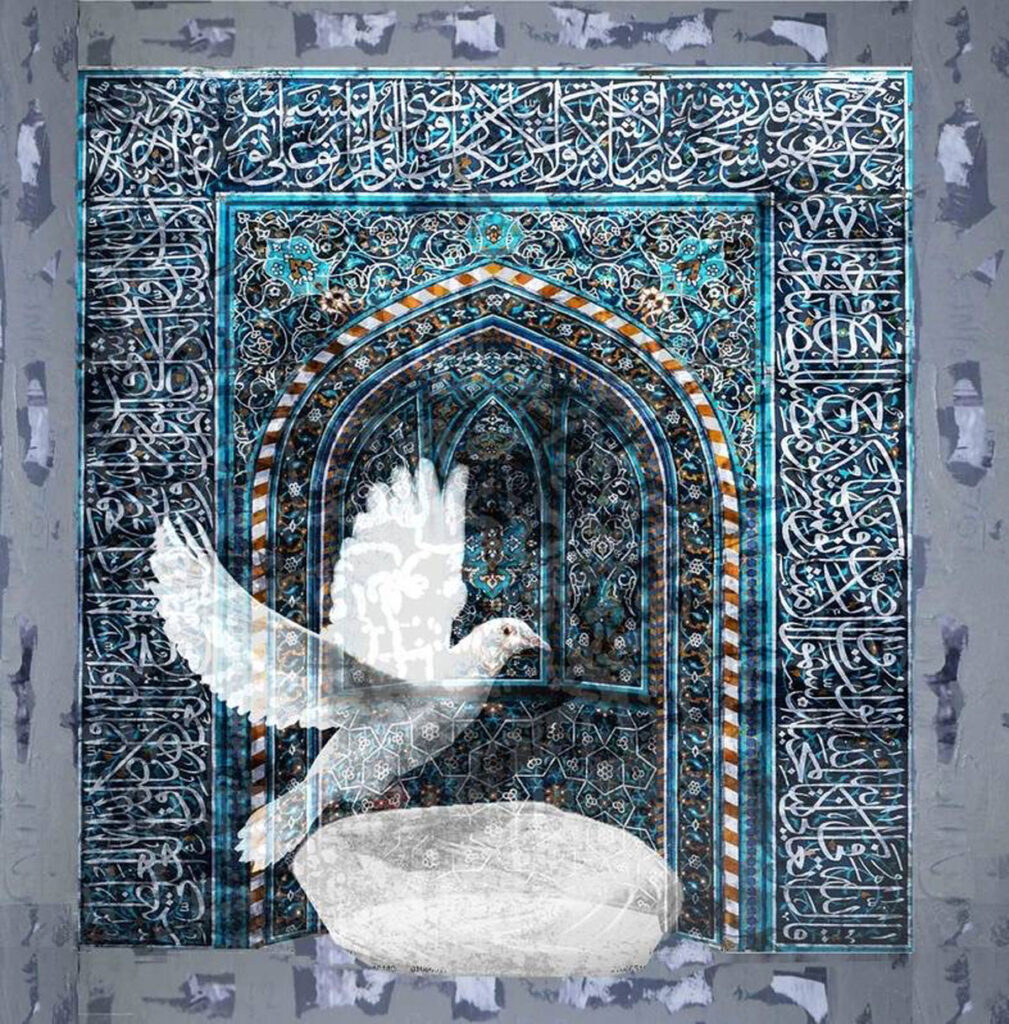

The Principle of Forms and Circles

As the most prevalent principle in the Sufism worldview, it was reflected in fine arts and architecture by preferring circles as in the arches, and waves as in Atairique. Arab calligraphy has also contributed to establishing this circular image by extending the letters and wrapping them together. Samer Akkach illustrates how the Cosmos in the medieval Islamic perception is a group of circles, the lowest of which are the sentimental and natural circles, and the highest of which are the metaphysical and angelic circles (Akkach, 2005, p. xviii) and if we were to depict those circles artistically, it would bring up a scene of utmost beauty and splendor. This wasn’t possible within an “iconoclastic” art culture, but it became later possible with modern art, especially with baroque. However, the artistic memory of baroque was present in the Arab Islamic culture, according to AAge Brandt, who states “Fretsz Strich has instilled the idea that the Baroque is a Spanish creation, and couldn’t have become such a notable movement without the Spanish contribution, as it extended throughout Europe. The foundation for this was that the Arab culture was so powerful, especially in Andalusia. The renaissance was just a phase, with no deep connotation, and the Counter-Reformation was violent” (Brandt, 1996, p. 101).

Ibn Arabi has often explained in his writing the Hadeeth of “Indeed Allah, the Almighty, created His creation in darkness, then He cast His Light upon them”, so if we were to agree that circle, wave, and shadow shrouded with light are the foundations on which baroque art and architecture were built, then we can comprehend how those elements were present in Islamic culture, as in the dimmed domes with the light crossing them through tiny glass holes. The Royal Hammam (bath) at Alhambra Palace provides an example of the light-sprinkled darkness via tiny star-like holes sparkling through the darkness. Light/Darkness, Hot/Cold, and Separate/Uniting, are one of the baroque elements in embellishing the insides of buildings. Ibn al-Jayyab of Granada, whose poem outlines the walls of the Hammam, says:

The heat of the fire inside is most pleasurable

And pure water falls within

Scatters of wishes are brought together

Just like water and fire have been

Waving or circling provides an escape for geometry and painting so they can avoid the boring patterns and pump life and motion into the image. Ibn Arabi’s book “Construction of Circles” is one of the most prominent Sufi books talking about the image position. In his book, he provides a theoretical ontology of the world system and the entanglement of humane and cosmological so that it brings out the beauty of all paintings and architectural elements. “God, when he showed me the true essence and core of things” and this is nothing if not a phenomenological principle in comprehending the essence of things by their externality. “He uncovered the ratios and additions” and this is an interpretational principle in understanding the ratios and the relations, “I wanted to integrate it in the sensual formation mold” (Pages 3-4) and this is an aesthetical principle in incarnating the transcendent idea in the sensible matter. Even if the book revolves around being, nothingness, names, and the beginning of the world, it is all aesthetical to begin with, and aesthetical to end with. It starts by integrating the abstract with the sensible, just like an idea gets embodied in a painting, architect, or sculpture, until it arrives to explain Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali saying “Nothing more refined than this world is possible”, which was aesthetically reflected in the harmony that distinguishes it. Creativity is the main purpose of all the wisdom sprinkled in every corner of it, the same wisdom that the humans try to simulate, with inspiration and geniuses, when they try to portray the world system in fine arts and architecture.

The purpose of these principles that distinguished poetry, fine art, and architecture are to refer to the perennial spirit of cultural structures. Perennial Philosophy is considered one of the applicable Sufism ideas in all of man’s history, not only for the cosmological dimension of the metaphysical and aesthetical shapes recurring throughout history throughout different cultures and religions, but also for the convergence of variants and their coexistence. This is what Akkach meant by achieving “concordance between all traditional forms” (Akkache, p.7). Eugenio D’Ors, the Spanish writer, mentions that there is an “Aiôn” which is the metaphysical and perennial that makes all cultures entangle by their mere distinction. Baroque, which D’Ors takes to a perennial philosophy level (He doesn’t regard it as just architecture and artistic style that appeared in Italy in the 16th and 17thCenturies then vanished), is this Aiôn that transcends through historical eras, and becomes perennial in various forms. Sufism’s view of the world believes in this Aiôn impact and vital role, and its ability to personify the abstract and achieve cultural coexistence. Thus, this Sufism vision, incarnated in architecture and fine arts, represents this perennial Aiôn that we experience when we see a painting or an architectural form, when we hear a melody, or when we embark on speculation or a contemplation journey, so much that it takes us away from our individual identities and nudges us to see the world’s phenomena in the light of united human feeling and oceanic sentiment.

References

- Ibn al-Khatib, Lisan Al-Din (1983), “Al Katiba Al Kamina Fi Man Laqinah Fi Al Andalus Min Sho’raa Al Ma’a Al Thamina” (The latent unit of poets of Andalusia during the 800s), annotated by Ihsan Abbas, Al Thaqafa Publishing House, Beirut. (In Arabic)

- Ibn Arabi, Muḥyī ad-Dīn (1919), “Insha’ Al-Daw’ir” (Construction of Circles), German annotation and translation, and publishing of the Arabic text by Neuberg, Brill Publishers, London. (In Arabic)

- Ibn Arabi, Muḥyī ad-Dīn (n.d.), Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya (Meccan Revelations), 4 parts, Dar Sadir Publisher, Beirut, (In Arabic)

- Al-Surayhi, Muḥammad Ibn-Yūsuf (1997), Diwan of Ibn-Zamrak of Andalusia, annotated by Muḥammad Tawfīq Nayfar, Dār al-Gharb al-Islāmī, Beirut, (In Arabic)

- Farghalī, Abū al-Ḥamd Maḥmūd (2000), Islamic Figuration: Origins, Islam Stance, Principles, and Movements, Egyptian-Lebanese Publishing House, Cairo, 1991 (In Arabic)

- Akkach, Samer (2005), Cosmology and Architecture in Premodern Islam. An Architectural Reading of Mystical Ideas, SUNY: New York.

- Brandt, Aage (1996), « Morphogenèse et rationalité : réflexions sur le baroque », in Buci-Glucksmann, Christine (éd.), Puissance du Baroque. Les forces, les formes, les rationalités, Paris, Galilée.

- D’Ors, Eugenio (1935), Los Barroco, French Translation by Agathe Rouart-Valéry, Du Baroque, Paris, Gallimard, 1936.

- Farooqi, Shafique (2014), The Tale of Drunken Flute in Whirling Dervishes, Farooqi Art Studio: Lahore.

- Gruber, Christian (2010), The Islamic Manuscript Tradition, Indiana University Press.

- Puerta Vilchez, José Miguel (2011), Reading the Alhambra: A Visual Guide to the Alhambra Through Its Inscriptions, Edilux.

Researcher, professor of philosophy at the University of Tlemcen (Algeria). Ph.D. in Arabic and Islamic Research and Study/ Mysticism and Interpretations, University of Provence (France) 2004, Ph.D. degree in Philosophy from Aix-Marseille University (France) in 2011 in the field of Practical Philosophy and Le quotidian.