As we wander through an exhibition or a museum, we come across paintings of faces and portraits which we often contemplate in terms of referring to specific people and embodying the memory of their passage in this world, whether they are holy figures (such as the Christian icons), real people, or imagined drawings. What we often forget is that drawing faces in the history of Arab art preceded drawing nature and bodies, and it was much earlier than female embodiment. From Daoud Corm to Mahmoud Sa’eed, Arab art was going through its first transformations which bypassed stylized Christian icons toward a realistic model that largely matches the face and body of its owner as if it were a reflection in a mirror.

This transformation which was firstly indicated by the Arab fine art was not only a reflection of iconographic tradition in which ecclesiastical iconographic heritage was almost literally restored, but it was also a reflection of the changes that were taking place within the Arab societies at different paces. The symmetric drawing of the face, starting from the specific human model (the picture’s owner), was indicating the birth of the individual and individualism in Arab societies, in parallel with the modernism’s intellectual transformations that were led in the same period by Arab thinkers such as Al-Afghani, Muhammad Abdo, Amin Qassem, and others.

Portrait and the Arab modernism stakes

While the viewer directly links the portrait to its owner, the birth of photography and its rapid spread in the Arab world as of the colonial period has liberated fine arts from this task. Nevertheless, portrait painting remained one of the main elements of the academic training. The face is not only the identity of the human beings, but it is also the home of their concreteness, the source of their identity, and their meaning in life and existence.(1) It is also the sign of their passage in the world, and this explains why many pioneering fine artists, like Rembrandt, were painting their personal portraits; they were trying to capture the transformations of their face and its expression of their progress in life because the face is the transformed geography of the human being.(2)

The face occupies a major rank in the concept of being. Without the face, there is no meaning of divine creation as envisioned by Islam, for example. Hence, we can realize the close relationship between the concept of creation and the divine depiction of His creatures. The word image in the Arabic language means the body and the face, and it also means what is visible- real or imaginary (imagination, statue, ghost, etching, or drawing). The holiness of the human face can reach the point of prohibition (tahrim) of photography in Islam which is, in essence, not absolute but it is a prohibition of drawing the identity of the human entity. We can understand the significance of the ‘hadith’ that recommends putting dye on the face of a drawing or the anthropomorphic object to turn it into a corpse without an identity, and thus disable its human resemblance and matching the Creator in the process of creation.(3) Perhaps this explains why the extremists did not destroy statues completely but beheaded them; the head is the home of the face and consequently the home of the human personal identity. In the same vein, the meaning of the two Qura’anic verses, “Everyone upon the earth will perish, * And there will remain the Face of your Lord, Owner of Majesty and Honor*” (26-27) cannot be understood and interpreted except in this context. The invisible divine entity cannot be expressed by anthropomorphism but rather by referring to the face as it is a metaphor for being and presence.

The painted faces that we received from the Arab-Islamic heritage remained faces in miniatures of a stylized nature with the aim of a suggestive and expressive embodiment rather than an accurate simulated one. The painted faces have similar features with the drawn ones, and they only take difference in age (boy or man), gender (man or woman), or species (animal, plant, or human)(4) from the visible object. This legacy is apparent in the beginnings of modern art in countries that remained in denial of photography, such as Morocco and Algeria. For example, although Mohammad Rasim learned photography from Étienne Dinet, one of the greatest orientalist artists in Algeria, Rasim’s paintings remained in conformity with the principles of stylization, despite some deviations.(5) In similar lines, the faces of personalities in the works of the first Moroccan artist, Muhammad bin Ali Al-Rabati, only seek presenting the social function of the portrayed characters as an expression of daily life aspects in Morocco at the beginning of the last century.(6)

In the Arab East, the Christian tradition has been practicing photography for many centuries in terms of reproducing the portraits of local saints. The work was done by traditional artisan-like photographers who were working according to the rules of stylized photography that preserves and reproduces the bodies of saints, their clothes, looks, and the ‘features’ of their faces. However, the emergence of modern photography announced the emergence of simulated photography, the birth of the individual separated from the church and the community, and uniquifying the artists who can sign their own works, unlike previous times when the works of the traditional photographers were unknown.

The works of Daoud Corm, Saliba Douaihy, and others from the first generation have socially accompanied the birth of the bourgeois individual and the Arab modernism earlier to what we used to call the Renaissance. Daoud Corm painted notable figures in Beirut using the oil and pastel technique on paper in a personal and unusual manner; he focused on the features and the social and professional position of the portrayed individuals. Among his most prominent achievements in this regard are the portraits of Pope Pius IX (early 1870) and Butrus Al-Bustani (1894). Daoud Corm also left us many paintings at the end of the last century such as those of Khedive Abbas II and some of Egypt’s notables.(7)

The same was experienced in the beginning of the twentieth century in Maghreb through the prevalence of photographic portraiture which announced the birth of individuality and celebrating it visually among notables and writers. Notables used to exchange pictures and write poems on the back of the portraits to celebrate anniversaries and declare personal identity.(8) However, the development of portraiture in the Levant did not have a parallel equivalent in the countries of the Great Maghreb, especially the Far Maghreb which did not have a Christian community, nor was it ruled by the Ottoman Empire, so it remained largely closed. The famous portraits in this region at that time count on the fingers of one hand, and two examples are the portrait of Sultan Mawla Abd Al-Rahman by Eugène Delacroix (1834) and the portrait of the leader Thami El Glaoui by the orientalist artist Majorelle (1918).

Portrait transformations: stakes of modernism and contemporariness

The art of portraiture or depicting the face (and personality) appeared in the East before the colonization of the Arab countries, thanks to personal efforts and the establishment of fine art schools, especially in Egypt, in 1908, in which Egyptian artists taught their students the arts of photography, including the portraiture. Paradoxically, the development of this particular art coincided with the development of photography, which, as we know, contributed to the democratization of the personal image. The development of photography studios in many Arab countries had a great impact on undermining the spread of portraiture and turning it into an artistic favor monopolized by eminent personalities. For example, the studio that was set up by the photographer Muhammad Selim in Cairo in the thirties of the last century was dedicated to the portraits of famous writers, such as Tawfiq Al-Hakim, artists, such as Kamal Al-Shennawi, dancers, and others.

The result of this unfair competition is the development of what is known as qualitative scenes that monitor daily life personalities as the case is with Mahmoud Sa’eed or Mahmoud Khalil from the first generation and those who followed suit. The fictional character has become more dominant in modern artistic creativity, and the aesthetic methods have become more distant from realism and from the face for the sake of more focus on portraying the body in its relationships as well as in its unity (the female body in Mahmoud Sa’eed’s, for example). With the ‘Art and Freedom’ movement, the displacement began to clearly occur not only from the face and body reference but also from the realistic figures in painting and sculpture. Surreal freedom was celebrated. Most of the portraits were carried out within the framework of an imaginary symbolic vision whose obsession was not to emulate a realistic figure but rather to conform with the framework of the aesthetic transformations that the modern fine art movement has known, starting with realism and then arriving at new experimental frontiers that reached abstraction by the fifties, with the Lebanese artist Shafiq Abboud and the Moroccan artist Al-Jilali Al-Gharbawi.

Portrait has moved from the external reference to the identity form and deconstruction. In this context, we can consider Bahgouri’s fine art portraits as a unique experience in contemporary Arab art. After spending many years crystalizing his caricature style, especially in Rose Al-Youssef magazine, Bahgouri manipulated his distinctive style to create fine art portraits inspired by his caricature world, and simultaneously, tend toward another displacement related to an expressionist formation that does not focus on features but creates distance with the reference model, if it existed. Thus, we can say that this experience is among the rare ones that work on the reference in a personal way that gives it a different dimension.(9)

In the same context, we can contemplate the experience of the Egyptian artist, Muhammad Abu Al-Naga, in restoring the faces (portraits) of the artist, Souad Hosni, and the singer, Umm Kulthum, using a complex serigraphic technique in which he re-reads the visual memory of childhood. This approach to the symbolic faces of our childhood imagination (and then to the audible and visual Arab art’s imagination) represents a renewed restoration of the face in its symbolic dimension as it is the representation that shaped the memory and stored the crystallization of many deep and influential meanings in it. While most artists, Egyptians and others, have dealt with the image of Umm Kulthum with much nostalgia and realism, Bahgouri, Helmy El-Tony (with his popular sense), and Muhammad Abu Al-Naga provide us with a new visual interpretation of this lyrical icon. It is no coincidence that Muhammad Abu Al-Naga’s approach is characterized by overlaying and multiplicity as if the image of the lyrical or cinematic icon can only be viewed through multiple visual brushes that render its identity a multiple one.

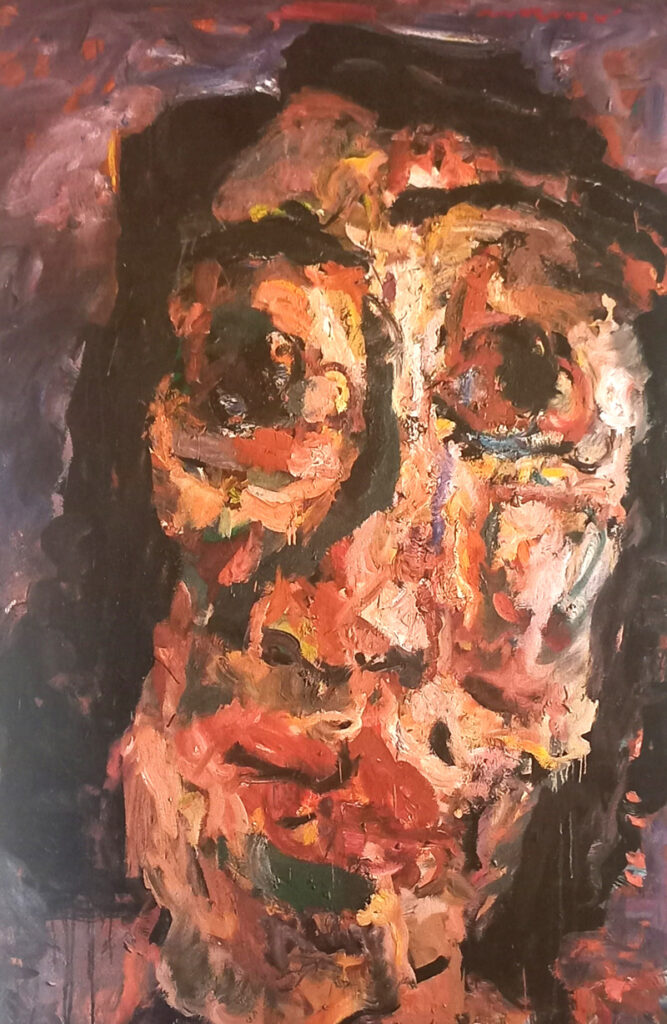

For Marwan Kassab-Bachi, working on the face is a central element in the formation of a painting. The faces in Marwan’s works are characterized by geography and expressive topography, which makes him compared to Edvard Munch, Georg Baselitz, and others. Al-Khatibi says about Kassab-Bachi, “Does he practice violence against himself? Yes, through a gentle melancholy that we can contemplate in this face/scene that he painted in 1974 which, swiftly and with deep concern, engraves the fate of the artist who has become a sign, a pollen, a scene, wrinkles, thorns, gloom, soil, stone, and grooves. The face, altogether, in its re-embodiment, stares at us deeply and suspiciously”.(10) Some of the faces almost explode in movement and transform in front of us to reproduce like an entity fleeing from identification towards hybrid brutality.

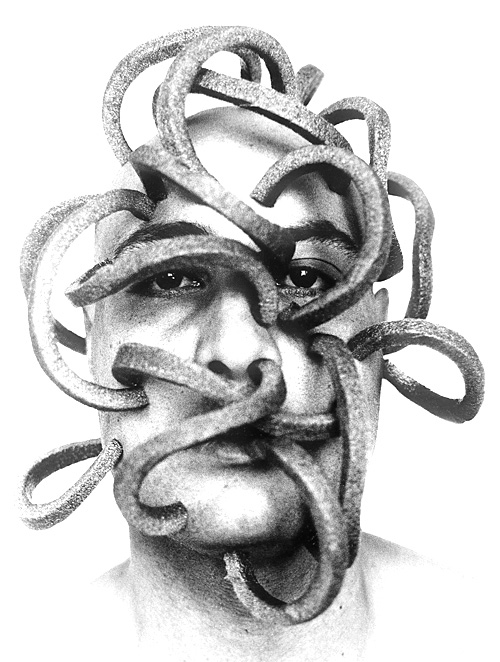

After these transformations, we are almost certain that approaching the development of portraiture in contemporary Arab art can be a probe for the development of Arab fine arts as a whole. The return to portraiture will take place differently for many artists according to new stylistics away from realism reference and in the direction of crystallizing something innovatively imagined in which it will become a new pilgrimage for identity corridors and pathways. This is sometimes done by restoring congruence with the real person in order to recrystallize self and its existential differences. The experience of the young Moroccan artist residing in Canada, Zakaria Ramhani, who exclusively works on faces, including his own face, can be considered a special experience in this regard. This artist has provided us with many self-portraits in different shapes and poses. The face in his paintings is not shaped in terms of features but rather in terms of kinetic components that are intertwined with expressive touches that resemble Arabic and Latin letters. “These letter-like symbols intertwine, mix, condense, and overlay as if to make us dizzy. If we took a single part of the portraiture, we would find ourselves in what looks like a maze. However, in the end, this whole is wrapped and harmonizes in color, movement, and shape to create facial features that we may recognize when it comes to a personal portrait, and definitely we recognize it when it comes to someone like the American president.”(11) In his early years, Ramhani’s portraiture was “simple” in terms of reference and kinetic composition, and then, with the succession of “artistic series,” his portraiture became complex, superimposed, reproducing, branching, and overlaying in the form of multiple portraits, one of which almost steals the meaning from the other.

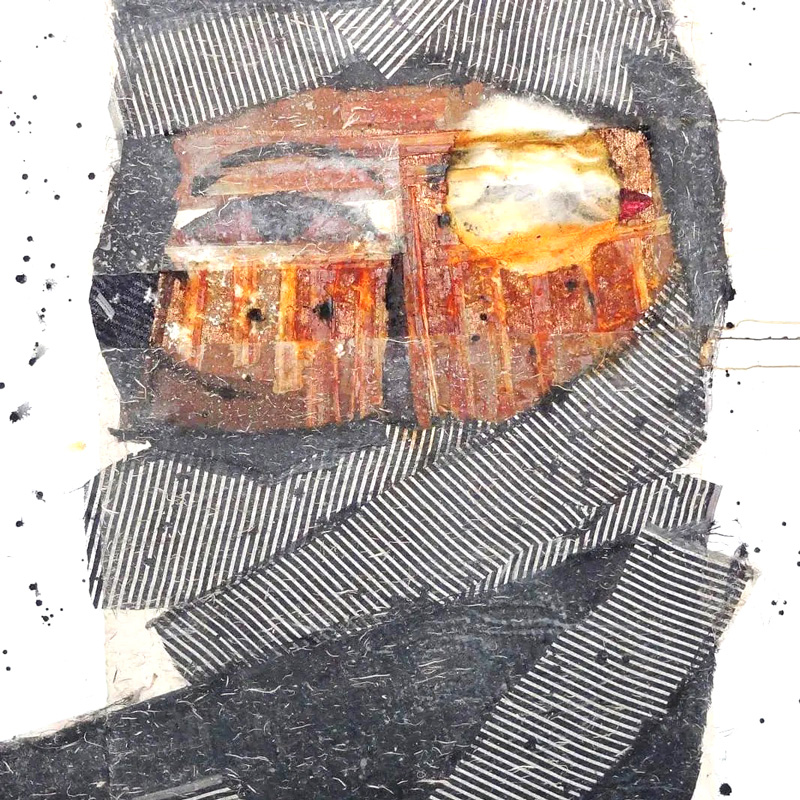

While many modern artists have practiced portraiture in its narrow form (the face) and expanded form (the body) in a referential, symbolic, or surrealist way, contemporary artists tend, through portraiture, to deconstruct the visual presence given to the object, and subsequently the identity in its mono-referential sense. In this context, we can include the expressionism of Sabhan Adam and the two Moroccans Aziz Abu Ali and Abd Al-Rahim Iqbi. While the first builds the object’s strangeness based on the dreary strangeness of the face in particular, the second and the third range between eliminating it completely, alienating it, or turning it into a strange bird’s head as if they were trying to fit it with an amorphous body with no complete organs. The alienated face appears as a metaphor for the extreme strangeness of the body and being.

Photographic portrait and the game of the imagined

Photography descended from portraiture, and it aimed at perpetuating people’s images. More significantly, it turned to be the visit and identity cards by which individuals are registered, identified, and enabled to move. Since the photographer “Nazar” immortalized the images of Baudelaire, Balzac, and other writers by the end of the 1980s, the fate of this new technique was to combine recording with capturing what is fleeting. This recording characteristic which Barthes calls “Reality Effect” is behind the return of contemporary photography to recording in the way to grant it an imaginary and symbolic nature.

Leila Alaoui, who was passed away while working in photography, began her experience with the pictures of unknown Moroccans in her mobile studio, and her experience ended, with the reconnaissance photography. Her experience with “The Moroccans” was a special adventure through which she sought to build her visual identity and her own affiliation- a Moroccan-French artist.

Leila Alaoui followed in the footsteps of the American photographer, Robert Frank (in his album “The Americans,” 1958) and his compatriot, Richard Avedon who was famous for his black and white portraits, to combine documentation with the aesthetics of new realism. When she started her project on “The Moroccans” through which she obtained her position in the artistic community, she aimed to deconstruct the exoticism that controlled the portrayal of the other and to build a different view that emanates from within. This experience was a difficult and complex endeavor made by many female Arab artists to deconstruct the colonial and orientalist(12) vision that still dominates our view of ourselves which reflects a kind of internal orientalism. Among these artists are the Tunisian Maryam Bouderbala and the Moroccans Lalla Essaydi and Majida Khattari who use photography to shape their artistic installations.

In the same context, the works on the face by the contemporary Moroccan artist, Hicham Benohoud can be considered as an essential component of his artistic career since his beginnings in the late nineties of the 20th century. The portraits of his students line up in an exciting reconnaissance show, and the manipulations of his own face and body convey a pluralistic existential experience. The Saudi artist Faisal Al-Samra resorted to portraiture to question the Arab Spring and to generally explore the cracks of the Arab entity. This shows that the return of portraiture to the contemporary Arab art is a new restoration of the its referential indications, a deconstruction of the unilateral concept of identity, and an immersion in its symbolic and existential connotations as the sublime sign of the human entity, which constitutes a fertile entry point for monitoring several aspects of life- political, social, and the intimate being.

1. David Le Breton, Les Visages. Une anthropologie, éd. Métailié, Paris, 2è. Ed., 2003, p. 43, 55.

2. David Le Breton, Les Visages. Une anthropologie, éd. Métailié, Paris, 2è. Ed., 2003, p. 187.

3. Farid al Zahi, The Body, the Sacred, and the Image in Islam, East Africa, Casablanca-Beirut, p. 2. 2010.

4. Kyriakos Papadoupoulos, L’Islam et l’art musulman, éd. Mazenod, Paris, 1979, p. 279.

5. Cf. Mohammed Khadda, Mohamed Racim, miniaturiste algérien, SNED, Alger, 1990.

6. Cf. N. de Ponchara, D. Rondeau, Un peintre à Tanger en 1900. Mohamed Ben Ali R’Bati, éd. Malika, Casablanca, 2000.

7. Edward Lahoud, Contemporary Art in Lebanon, Dar Al-Mashreq, p. 1, Beirut, 1974, p. 15-16.

8. In this regard: Muhammad Amin Al-Alawi, “Indications of the Use of the Photographic Portrait in Morocco,” Meknasa A. Magazine. 8, 1992, p. 83. https://islamonline.net/archive/ [4.02.2023].

9. Farid Al Zahi: “From the Image to the Visual, Facts and Transformations”, The Book Cultural Center, Beirut-Al-Dar Al-Bayda, i. 1, 2017, p. 203-207.

10. Abdul Kabir Al-Khatibi, Contemporary Arab Art. Introductions, translated by F. Al-Zahi, Okaz publications, Rabat, p. 1. 2003, p. 35.

11. Farid Al zahi, “From Image to Visual,” p. 294.

12. Farid Zahi, Les Métamorphoses de l’image. Ecrits sur le visuel, 1 ère éd., Marsam, Rabat, 2015, p. 97-103.

Moroccan writer, translator and art critic. His intellectual work is divided between critical research and translation. He earned a BA in Philosophy and Psychology in 1983 and a Certificate of Advanced Studies in Comparative Literature in 1984. In 1987, he completed his third-year PhD in Islamic Studies and Civilization at the Sorbonne University.