Since its formation in 2009, through its exhibitions, programs, publications and collection, Sharjah Art Foundation has been cultivating diverse narratives on global art, thereby expanding prevailing historical discourse by offering multiple points of approach and departure. The Foundation’s close networks and longstanding friendships with neighboring agents across the mission of platforming artists and thinkers whose intellectual legacies can be traced beyond Western epistemologies. Pop South Asia: Artistic Explorations in the Popular, is the most recent outcome of such initiatives…

Hoor Al Qasimi, President and Director, Sharjah Art Foundation

When “Art becomes the reality itself”, artists seek to produce art in which the possibility for its real intervention is reduced, thus leaving behind the basis of its configurations and its sentimental and aesthetic dimensions. While this is hence considered an unusual and untypical art, or even regarded as the “Anti-Art” but it is simply a popular art that conveys many of the popular concepts and culture.

The word Pop is an abbreviation for population, meaning the thing that is popular. It was used by the English art critic Lawrence Alloway, between the years 1945 – 1957, to identify the artworks of a group of independent young artists who opposed the no-shape art, and were demanding the return back to modern life manifestations and the popular culture mediums, and pop art or popular art is one of the Anglo-Saxon art trends that emerged in the late 50s in England, and spread widely in America in the early 60s of the last century.

Pop art was known to be a movement that was against the dominant cultural system. It came to oppose cultural institutes such as museums and to go against what was known as elite art. The movement worked towards fostering popular culture and consumerism styles, and publishing them via the media and audience communication. Popular art had several manifestations, one of which is the reproduction of pictures, and its connections to the social and political issues of society, and on the list of its most prominent figures are Richard Hamilton, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Jasper Johns, Robert Rochtenberg, and David Hockney, among other.

Pop art is known for its many trends, techniques, and styles, which are so many to count. Marcel Duchamp used the term “New Dada” to describe the set of art trends and movements that ensued abstract expressionism, on top of which is pop art. Of those, we mention: Assemblage, Installation, Ready-made, The Art of Found Objects, The Art of Waste Materials, The Art of Recycled Materials, Media Art, Photography, Art of Packaging, Graffiti Art, Video Art, and Kitsch Art…

The Pop South Asia Art

Visual arts in South Asia were not to receive a great deal of attention, some might even go further to assume that this kind of art does not exist in those broads. Furthermore, these countries were always going through conflicts and struggles to an extent where stability and safety can no longer be found. Yet, this did not deny them the right to have real art, in addition to attempts, experiments, and evolving different styles and trends of visual arts, so that after the right conditions were available for modernism, civilization, cultural and intellectual exchange, many art trends and cultural practices, which allowed many artists to express whatever omens they had in mind, and whatever concerns they could possibly imagine. The art exhibition ” Pop South Asia: Artistic Explorations in the Popular” is the culmination of the artist’s creative vision, while showcasing their diverse artistic productions of visual arts, photographic images, video tapes, Assemblage pieces, and others, where each one of them narrates, in their own style, their reality, daily life, and struggles, after Many issues are becoming more concerning for the artists, issues such as citizenship and equality, visual protest culture, the political aspects of pop art, in addition to the issue of how national countries systems are controlling the individuals’ movement through and inside their borders. for that, the artists resorted to utilizing irony and humor to criticize those dilemmas.

Organized by Sharjah Art Foundation and Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi, “Pop South Asia: Artistic Explorations in the Popular” exhibition, curated by Iftikhar Dadi and Roobina Karode, took place in Al Mureijah Art Spaces, Sharjah. the exhibition is one of the first major exhibitions to provide a substantial survey of modern and contemporary art from South Asia engaging with popular culture. Spanning works from the mid-twentieth century to the present, the exhibition will showcase artists addressing complex issues facing the self and society through irony, play, and humor. Weaving an intergenerational dialogue through more than 100 artworks by artists from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and the diaspora, Pop South Asia navigates multiple and diverse themes. The exhibition spotlights artists who intervene in the aesthetics of print, cinematic and digital media, alongside those engaging with devotional practices, crafts, and folk culture; it presents artists addressing modes of local capitalism, from large-scale industries to vernacular ‘bazaars’, in company with those commenting on identity, belonging, gender, politics, and borders.

The Curator Iftikhar Dadi indicates that the exhibition “focuses on a major but largely unexamined development in the modern and contemporary art of South Asia, its engagement with popular culture from the mid-twentieth century through the present. The rapid development of capitalism, urbanism, media, technology and mass politics since the late nineteenth century has engendered multiple resonances and fault lines in the complex societies of South Asia, providing openings for artists to engage with the popular social and culture developments. South Asia serves as synecdoche of wider developments across the Global South, which continues to modernize and urbanize, and wherein the ambit of pop art is not confined to what is commonly understood in a Western context as engaging primarily with the late capitalist consumer culture and media imagery”.(1)

Many Afghan artists found their own style to express themselves, at a time when safety and real stability are scarce. Hangama Amiri (born in 1989 – Peshawar) is one of those artists, who worked under exceptional circumstances. . Hangama Amiri was born at a refugee camp in Pakistan and was displaced many times while growing up due to the conflict in her country, Afghanistan. when she was still a young refugee, art provided a resort in which she felt safe and was able to comprehend the course of events around her.

Her artworks mainly revolve around the concepts of citizenship and the ways in which gender values, social standards, and geopolitical conflicts affect the daily lives of Afghani women. additionally, her colorful textile artworks explore issues such as women’s rights, homeland, and memory. she tries to embody power in representing daily used items, such as a passport, a vase, or postal cards with celebrities on them.

In her installation artwork “Bazaar” 2020, the artist refers to the major social and cultural transformations resulting from the collapse of the Taliban regime in 2001, which included the freedom for Afghan women to work and express themselves. the artist tries to recall her childhood memories, and the times she roamed around shopping areas in Kabul along with her relatives of girls and women, at a time when the management and properties were owned only by men. it is an invitation for the viewer to relive that reality that has been reinstalled as some sort of vanity, she evokes that historical period of time through huge textured installations that embodies the commercial sites and the traditional Souq.

Hangama Amiri’s adaptation of Kitch art was within a framework of a critical approach to the society she lives in. Kitch is a german word that came originally from the Yiddish language and it means to (sweep up or scrape up mud from the street). the word was used by art merchants in Munich after the second half of the 19th century to describe cheap works of art. later, at the beginning of the 20th century, it was used as an artistic term to refer to the art of recycling and reusing worn-out objects, in addition to things in poor taste, as a reference to the materialistic spirit and the industrial and molded world, and daily consumption, in order to introduce an art that beautifies the reality, so that Kitch is not perceived with art standards, but rather a social issue because aesthetics alone were no longer enough, and the world, according to Kitch artists and theorists, is in real need for real art.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and Twitter have assigned Hangama Amiri the mission to design the emoji for World Refugee Day, celebrated on June 20 every year. this was the first time where a refugee designs this emoji, and it features a blue heart floating between two cupped hands to symbolize protection and solidarity.

And as it always is, we saw that each of the Afghani artists found his own way of expression, and so do indian Artists. To highlight that, one artwork worth mentioning is one by K.M. Madhusudhanan (born in Alappuzha, India, 1956) titled “Authority and Knowledge”. the artwork is constituted of a series of paintings, all painted from his memories of collecting light matches stickers and hand-made cigarettes. the paintings simulate the designs of ancient merchandize packages, and imagine alternative histories, so the contrasting historical narrative showcases many symbols for authority, violence, and imperialism, all coming together to constitute a screaming contradiction with the recurring statement “safe light matches”. it is worth mentioning here that inventing light matches came at the expense of many lives during its development stages, which lasted for two and a half centuries, not to mention the victims of the fires resulting from its misusage.

While artist and writer Ijaz ul Hassan (born in Lahore – 1940) is known for his provoking politically-themed artworks, in an attempt to push his people to awaken and defend their rights. the themes of his artwork revolve around human rights and women’s rights in particular. his painting “Tah” carries symbolic meanings revolving around the important role women play in raising generations, preserving values, and defending them. in his piece, he displays a cinematic poster for the famous Pakistani actress Firdous and a picture of a mother fighting in Vietnam War, which is a symbol for women liberation and supporting the protesting movements against war.

Artist Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran (born in Colombo – 1988) is unique for his deep-rootedness in the ancient culture of his country, the thing he utilized in criticizing the social and political conditions, which is going through racial divisions and Religious fundamentalism. in his artworks, he speaks about the issues of gender, race, religion, and rituals, by making ceramic sculptures of imaginary strange-looking characters, which are an embodiment to the conflict among firm beliefs and modernism, which is close to his methodology in religion and culture.

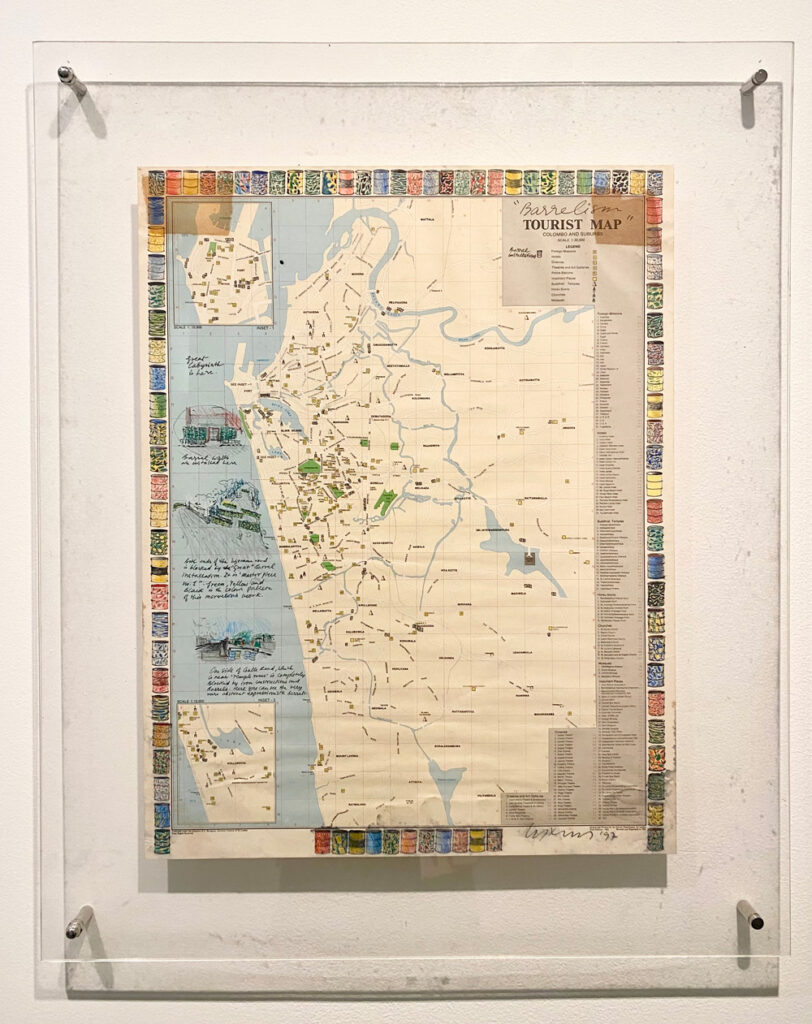

Artist Chandraguptha Thenuwara (born in Galle, Sri Lanka – 1960), in some of his artworks, narrate the story of “Black July”, which entitle the brutal massacres carried out against the Tamil on July 23, 1983, and lead to genocide and massive destruction in Sri Lanka. The artist is well known for his style, called Barrelism, which opposes war, and metaphorically represents the barrels used at security checkpoints that were installed back in the middle of the 90s in Sri Lanka, following the civil war (1983 – 2009). his artwork ” Barrelism Tourist Map” features a real tourism map of Colombo city, published by the Department of Tourism as a demonstrative tool to show the locations of barrels roadblocks and checkpoints. while his artwork “Barralscape” (1998 – now) is an installation piece that carries a call to protect the homeland and preserve it, it includes ready-made barrels colored in black, green, and yellow, pinned in a maze-shape to block the road traffic.

References

1. Iftikhar Dadi: “Pop South Asia: Artistic Explorations in the Popular”, Sharjah Art Foundation, p. 316, 2022.

Dr. Noha Farran is the Founder & CEO of ‘Thinking Art’ Foundation’, Historian, Professor, Cultural Strategist, Researcher, Curator, Visual Artist & Chief Editor of Al Tashkeel magazine. Holding a Ph.D. with excellence in the 'Art & Science of Arts', an MFA in Fine Arts, and an MA in the philosophy of art, she has authored numerous published books and research papers documenting art in the Arab World.