Rebellious Steps

Marcel Duchamp (1968 – 1887) is an established reference in any conversation about contemporary arts. The French artist spared no effort to come out of the modern artist suit to be regarded as contemporary, so much that Picasso considered him a sabotage and he was not sad to hear about his death. “He was wrong” was what Picasso said, who was the inventor of modern art, even if Paul Cézanne is considered the Father of modern art.

We can compare Duchamp with Picasso, which might upset the latter. Duchamp himself was also an inventor but in some place else, a place that has nothing to do with painting, even contradicts it, although he was a great painter. He left painting with no intention of coming back because he believed in the principles and values of Dadaism, and he didn’t want to be a surrealist like other Dadaists. Duchamp’s “Dada” was a constructive event, he awakened new forms of art that were asleep or hiding under the pillow, so even if they emerged from time to time, soon they’d go back to sleep. This is what happened to Joseph Beuys with his social art and Fluxus art movement during the middle of the 60s. Also the same happened to the “Art & Language” group, which was founded in Britain back in 1968.

Duchamp invented contemporary art, but what is meant by contemporary art? The alteration of vision modalities.

Each one of those arts carries a name; “Conceptual Art” “Performance Art” “Land art” “Video Art” “Installation Art” “Photography” “Physical Performance” and the list goes on because of the rebellion aiming to take beauty down in favor of idea. Duchamp accomplished what Dadaists couldn’t even imagine in one lifetime. For which he deserves to be an icon for contemporary arts, even if his influence came a bit late. The world was not ready in the 60s of the last century to accept Joseph Beuys, who was expelled from Kunstakademie Düsseldorf over accusations of offending the educational systems and traditions. He had to wait 20 years before contemporary arts could become visually acknowledged facts. For an art to be contemporary, it has to be the art of today. However, postmodernism imposed certain standards, which are not related to aesthetical tastes, but went far beyond them to be a huge alteration in vision modalities and ways of thinking. Joseph Beuys, born in 1928, died in 1986 after causing a shake even bigger than the one Duchamp caused, who will be regarded as the founder. Beuys’s prophecy had gotten him to New York where he did his physical performance “I Like America and America Likes Me”. New York was the new Capital of Arts, and he viewed it as the most acceptant city of contemporary arts, regardless of his constant political criticism of America.

In the Way to Internationality

Contrary to what happened on the art modernism relation level, the Arabian artist never hesitated to inspire the roles, origins, and manifestations of postmodernism via contemporary arts. Hassan Sharif, after he finished his studies in Britain in 1984, came back and started advocating the shift that contemporary arts can induce being the Arts of Today. He founded “The Five” group, which included, besides himself, “Mohammed Kazem, Hussain Sharif, Mohammad Ahmad Ibrahim, and Abdullah Al Saadi”.

The group was a collective form to expand the circle of this new knowledge in art, and they envisioned a different status for art in the society on one hand, and the relation between the artist and things around him on the other, especially everything that’s common, consumed, neglected, and discarded as non-art material.

The groups reconsidered the way we look at art in terms of being able to induce a visual shock, and they changed the technics by using materials that were regarded as non-artistic before. If we followed this phenomenon, led by Hassan Sharif, with the passion of an artist and the spirit of a critic, we would notice a never-seen-before turnout among Khaliji artists over the following years to adapt playful and troubling practices corresponding to contemporary visual arts. This could be seen in the experiences of Kuwaiti artist Munira Al Qadri,

Saudi Artists Faisal Samra and Abdulnasser Gharem, Emirati artist Ebtisam AbdulAziz, and Bahraini artists Rashid Al Khalifa, Anas Al-Shaikh, Waheeda Malullah, and Zuhair Al-Saeed. These practices have paved the way to internationality for a numerous number of Arab artists such as “Mona Hatoum, Mounir Fatmi, Diana al-Hadid, Lamia Joreige, Kader Attia, Ghada Amer, Sadek Al Fraji, Al Fadel, Akram Zataari, Walid Sadek, and Lara Balad”. What the Arab artist couldn’t achieve over more than 100 years, was done within a few years.

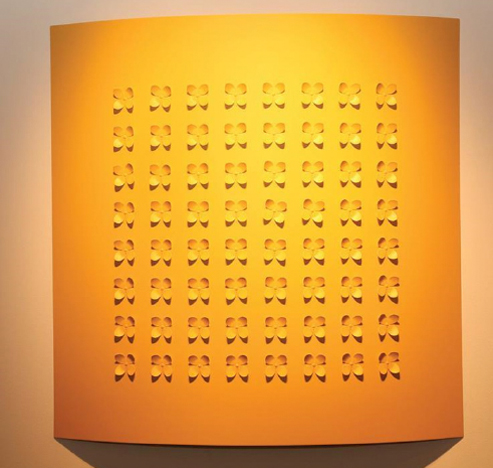

Ebtisam AbdulAziz and The World of Numbers

“Nothing in the streets attracts me, but numbers.” Based on this saying, the reduction appears to be at its peak with Ibtisam AbdulAziz (1975). Since she does not care about pictures, she tells her biography through clips extracted from her reality, but this does not mean that these clips contain a particular inspiration. Next to the numbers that the artist used to see during her tours and make mathematical equations out of them, there were also the things that she was keen to collect as significant finds. Empty bottles, cans, children’s toys, wood scraps, and other discarded materials that have been thrown away.

The artist says, “I collect these items, wash and clean them. During that, I feel like I’m washing dumped corpses. I then paint those materials white and integrate them into the artwork.”

What Ibtisam Abdulaziz has done is a kind of risk, in order to furnish a world that was not inhabited before, even though all of its materials have been borrowed from our world. This is an artist who restores dignity and respect to forgotten moments.

The artist thinks of the life of her materials, not of the materials themselves.

This is a life that gives us an idea of the environment that embraced them then denied them when they were consumed, but from the artist’s point of view, they still had a unique charm.

Because of the widening circle of contemporary art practice among Arab artists, it is not required to provide a critical review for all the contemporary Arab artists. However, it is possible to identify some of the features of this unique movement by highlighting the attempts of the most famous artists at least. From my point of view, the Arab artists had understood very well what it means for art to be contemporary. Therefore, their experiences can be viewed on one hand as a serious and high-level contribution to liberating the Arab artistic cognition from the authority of the old aesthetic taste, and this idea was never hostile to that taste. But we have to admit that the Arab artist was brave and daring when he discovered his ability to modify the modern taste and stand amidst its storms.

Mona Hatoum is an Artist with an Identity

Mona Hatoum (1952) has managed to shatter the idol of her local identity despite her need for telling some story to somebody. She claimed her spot as an international artist, and her name today cannot be disregarded when talking about contemporary arts.

Some believe that including her name on the list of British artists was the reason behind the interest she received from museums and international art meetings for her work, but this is not entirely true. Hatoum has an approach that transcends the personal to the public so much that personal issues can become issues of global impact.

It is not easy for an Arab artist to reach the world rankings and be listed as one of the most famous contemporary artists. One obstacle might be market experience, which cannot be obtained by anyone. Another one could be the museums, which have their own standards apart from the common concepts of art.

Mona Hatoum is of Palestinian origin, but with British nationality, that’s a point in her favor, as many art encyclopedias present Hatoum as a British artist. However, on the level of contemporary arts, identity is no longer meaningful. Still, Hatoum embraced her Palestinian identity to become an artist with a cause. This is what distinguishes her from other contemporary art artists, to have a cause that is, at the same time, an identity.

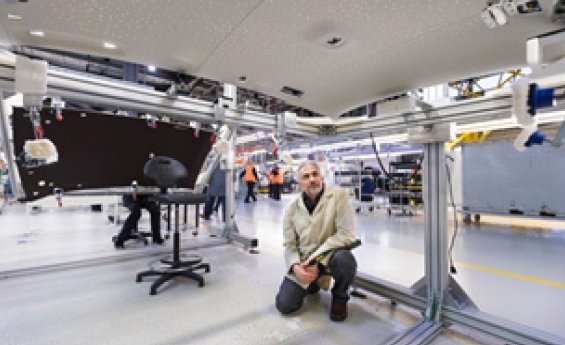

Rashid Al Khalifa and Post-Abstractionism

In 2010, Rashid Al Khalifa (1952 Bahrain) held an exhibition entitled “The Convex Plate: A New Perspective.” The exhibition included fifty paintings. Describing what prompted him to move to that stage, which some considered a leap into the unknown, Rashid says, “I have changed a lot, and this makes me happy because these changes help the artist to move and develop. Whoever refrains from doing that shall remain in his place, and this is wrong because the person has to search for all that is developed and new. If we look at the history of great artists, such as Picasso, we see that he used all the painting methods and tools he could, drawing on wood, ceramics, and paper, and even using coffee as a material for painting. The rule says: Search…search…then keep searching, and you must find something.”

This is the conclusion that the painter arrived at, as he moves decisively toward a comprehensive and complete abstraction. Forty years of painting were enough for nature to lose its dominant role as inspiration in artwork. Such transformation does not occur unless it came from an inner need, dictated by the circumstances of the painter’s relationship with his craft. One might say that “Rashid has changed”, as a matter of fact, those were his words in the exhibition when he announced his final transition. However, a keen observer of his stylistic transformations would certainly see that the ties and links between what he is doing today and what he was doing yesterday have never broken. Rashid is the type of artist who explores the transformations of matter with all their magic and thrill, just as he did when he speculated on the transformations of visuals. Today, Rashid Al Khalifa is the most experimenting contemporary Arab artist.

Lamia Joreige and the Time of War

Since Lamia Joreige (1972) joined the artistic scene after the civil war (1975-1990), she believes that the purpose of her existence was to gather the facts about that mysterious era of Lebanon, in which the Lebanese people fought, but with each one was holding a different image of Lebanon in their minds. “Records of Ambiguous Times” was the title of her exhibition, which she held in 2013 in Beirut. This exhibition was an attempt to display the past with the future on one plate, embarking on a journey to find that lost time.

“Were we losing a part of our collective memory at every moment of war?” That’s a question that Joreige will always hold, with no hope of finding an answer, neither in the past nor in the future. That is because both are cloudy, and no one is willing to admit it to history. None of the Lebanese was willing to say “we made a mistake”? Joreige sees that “Everyone has made a mistake,” but it’s a mistake that doesn’t get recorded in history. A part of the equation is missing, it could be a number, a word, or an ambiguous sign. Beirut, which the artist pursues with the “hidden camera”, is still hiding in gray and ambiguous times. The ruined city was forbidden to name the vandals. When everyone is absolved of guilt, there is no longer a killer, but the dead man is still re-living at the moment of the murder. For Joreige, that moment is her historic moment. Not because it is related to a loss, and neither because it gains a value by retrieving an aggressed right, but mainly because it is now an archive. An archive of a nation that can only be identified or introduced by a memory being a traditional heritage.

Sadiq Al Faraji and a Picture of the Past

All that Sadiq Al-Faraji (1960 Baghdad) does is an attempt to mend what was torn, with no hope of ever reaching the whole picture. Therefore, brief tales, hidden under a thick mask of violence, dominate an important aspect of his world, so much that they become the invisible thread, leading him to his destination. There, where his Qareen still resides.

Al-Faraji is looking for a recipient to join him in his attempt to escape the labyrinth of memory, and he often provides that recipient the opportunity to choose among pictures, films, writings, stories, and sounds that he makes by imagination.

The present will be as full of visions as the past, which has passed as if we had not lived it. Al-Faraji insists on holding on to that past so we can have faith that everything can be new through art.

Monira Al-Qadiri and the Desert Fantasy

Monira Al-Qadiri (1983 Kuwait) combines the spiritual suggestion with the inspiration of nature, whose existence does not separate the person from his surroundings. The artist who knows, for example, what the desert is, with all its psychological and visual influences, can relate, in an interrogative way, to the imaginative entities that have passed through this space, which is closer to an idea than to an absolute.

Al-Qadiri sought to apply the elements of social art to her society, in particular, and the Gulf societies in general, that is because she found the fertile ground that helped her a lot in linking the idea with the image. It is a dialectical relationship that links the environmental, the social, the political, and the cultural aspects in a shocking artistic form. This relationship has been a challenge for her.

Monira Al-Qadiri does not look at the desert with Western oriental eyes, but her trips there weren’t without a Western imagination that raises her local instinct to the levels of renewed discovery. This is a kind of knowledge that cannot be neglected or considered in part. The artist does not look for traditional terminology in the desert as much as she wants to unite with the cosmic scenes that unite the human being with nature. This is an attempt to revive a deep relationship in which both parties find the purposes of their lives when they’re united.

Randa Maddah and the narrativesof the place

Randa Maddah was born in the village of Majdal Shams in the occupied Golan in 1983. After completing a course in sculpture and painting at the Adham Ismail Center in Damascus in 2003, she moved to the Faculty of Fine Arts at Damascus University to study sculpture between 2005 and 2007. After that, she joined a workshop held in Jerusalem to learn the art of graphics. Her art products varied between painting, sculpture, and filmmaking.

The artist held her first solo exhibition “Hair tie” in Ramallah in 2016. This exhibition included sculptures executed in bronze, clay, and gypsum. Her second exhibition, entitled “Restoration”, was held in Paris in 2018, and included works carried out by video and photographic technicians, in addition to the completion of concrete works. In that exhibition, the artist highlighted the demolition and restoration approach. The realistic demolition of the place and the failed attempt to restore it from memory. She also held an untitled exhibition in the “Europe Hall” in Paris during her art residency there. This exhibition was devoted to works executed with pencil on paper. Randa received the Excellence Award from the Japan Takefuji Foundation. Maddah focuses in her work on the traumatic narratives of the relationship to a place that has been intentionally hidden.

Abdel Nasser Gharem and the Furious Conclusions

Abdel Nasser Gharem (1973 Saudi Arabia) became famous when one of his works, “The Message of the Messenger” was sold at Christie’s auction in Dubai for “842,500” dollars. He chose to be a conceptual artist, which leaves no doubt that he is refraining from entering the market by appealing to the common aesthetical taste. It is clear that he is not displaying his artwork in order to sell it.

Just like Joseph Beuys, the German artist, Gharem follows the philosophy of “social art”. A method of artistic thinking that stands against separating art from the current problems of life, but he does not describe these problems directly in a socialist realism manner as much as he tries to reach their conclusions through shocking scenes dominated by anger. This suggests that this method does not ignore the pure façade of politics, but refrains from getting involved in its outdoes.

Gharem represents a new group of artists in Saudi Arabia who think about art in its global context. However, what is surprising and comforting is that these artists, having absorbed the “global” with all its conditions, are now declaring their “locality”, which is their intellectual and aesthetic power that can present its conclusions to the world.

Faisal Samra and the Story of Nothing

“I want my themes to have multiple entrances and layers and to be read in an incendiary and direct way, and also philosophically and spiritually,” says Faisal Samra (a Saudi born in Muharraq, Bahrain in 1956). In his London exhibition “Build. Destroy. Rebuild,” the artist appears in the film as he smashes a chair, a symbol of governance. Even though he mocked, in his exhibition “global warming” what was called the Arab Spring, in that exhibition he ends the official tale with a scene in which he destroys the chair so that nothing remains. Nothing could indicate power, so there is nothing but chaos.

What cannot be seen amidst the lies of politics is confirmed by reality. The regimes have fallen, but the idea of authority has fallen with it, and now there is “Nothing” left. The artist carries his ruptures from the past to the future through the present. Samra analyzes what has happened to Iraq since 2003, and finds the “Nothing” that he saw coming, and this “Nothing” can only be the wreckage of a chair.

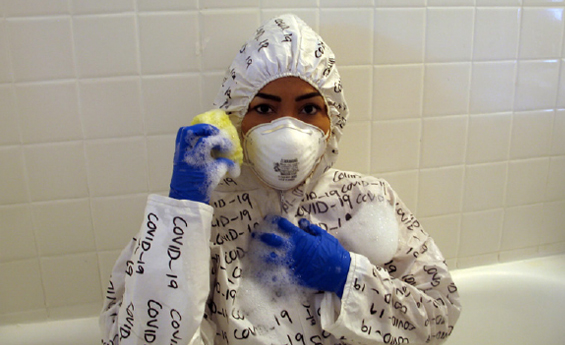

Raeda Saadeh: The Leading Actress in her Films

Raeda Saadeh was born in 1977 in Umm al-Fahm village, Palestine. She studied art at Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem and obtained a master’s degree. In 2000, she won the Young Artist Award organized by the Abdel Mohsin Al Qattan Foundation in London.

Her artistic interests are distributed among the art of installation, composition, physical performance, video, and photographic filmmaking.

This enriched her experience of looking at the outside world in terms of being able to transform it into concepts using a diverse mix of techniques. For example, she mixes physical performance and video art when she is the leading actress in her films, and she also mixes photography and physical performance when she is a model for her images, which often borrowed the visions of others to make displacements that serve as a contemporary personal interpretation.

Poet and art critic, born in Baghdad and lives in London. He has seven books in poetry, 12 books in art criticism, and 14 books of biography and travel literature.